NIRUPAMA, a child-widow, is dying in a dilapidated hut, far away from her village. She has been thrown out of society, a society for which she has sacrificed so much in life. And now her people have excommunicated her, declared her an outcast. Her fault? She has is in love with a man, a luxury a widow cannot afford. As she gets into trouble, her lover instead of defying society abandons her. At this juncture a rebellious young writer defies society and comes to her rescue. But it was too late for the hapless young woman. The young man watches her die slowly in front of him. The sheer dejection in her eyes, the misery, and the tragedy of it all would haunt him all his life.

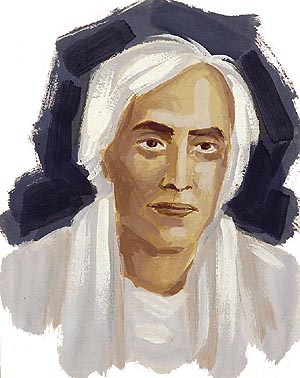

This was not a scene from one of his great novels, but a true incident in the life of Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyaya, one of the greatest writers India produced in the 20th century. A non-conformist to the core, he was at odds with decaying societal traditions all his life.

This was not a scene from one of his great novels, but a true incident in the life of Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyaya, one of the greatest writers India produced in the 20th century. A non-conformist to the core, he was at odds with decaying societal traditions all his life.

Like most creative people, Sarat Chandra's life was plagued with miseries. "My childhood and youth," he once recalled, "were passed in great poverty. I received almost no education for want of means." His father was a drifter who could not find a regular job; this forced his wife to take shelter in her father's home in Bhagalpur. In 1881 when Sarat was five, he was admitted to Pandit Pyari Bandopadhyaya's Pathshala in Devanandapur. He was a very mischievous child, and his teachers tolerated him only because he was too brilliant for his age. He joined hand with his equally unruly friends and formed a gang. They stole from farms and orchards, and shared the spoils with the needy.

During this phase he got attracted to an equally naughty girl named Dhiru, and this was a friendship he never quite forgot to his end. He painted a vivid picture of Dhiru in his novel Srikanta. But although he played truant too often during his school life, Sarat Chandra passed his middle class examination with merit and obtained a double promotion, and was welcomed by Durga Charan M. E. School.

One of the earliest influences on Sarat was the book Sansar Kosh, which had mantras and charms that were supposed to be a cure for all the problems of life. Somewhere down the line he started writing his first short story Kashinath which he later developed into a novel. He wrote many stories during this phase but only Korel has survived. He inherited the art of writing from his father who was as unsuccessful in writing as he was in other spheres of his life. His father wrote many stories and novels, but unfortunately completed none of them. Sarat would read them and wonder what the end climax of the story would be. Unfortunately all of his father's incomplete stories have been lost. "From my father I inherited noting," Sarat later wrote, "except, as I believe, his restless spirit and his keen interest in literature. The first made me a tramp and sent me out tramping the whole of India quite early, and the second made me a dreamer all my life."

As he grew up a severe plague broke out in Calcutta, but Sarat Chandra left in time to live with his uncle in Rangoon. Unfortunately, his uncle died of pneumonia, and Sarat became destitute one again, and was once again insecure and out in the streets. What followed was a string of unsatisfactory jobs, and a number of other experiences not condoned by society. But in spite of all the hardships, he did produce one masterpiece of literature after another, namely: Charitraheen, Devdas, Griha Dah, Ses Prasna, and so on, amounting to a mind- boggling list of more than 30 full-length novels, dozens of short stories, plays and essays. Apart from writing about the evils of society, he also wrote novels reflecting the patriotic spirit of his times.

In his last days when he was asked to write his autobiography he said with characteristic straightforwardness, "I cannot write my autobiography. I am neither that truthful nor that courageous." And on one occasion when Rabindranath Tagore also made a similar suggestion, Sarat replied: " Gurudev! Had I known I would become such a great man, I would have lived a different sort of life.

http://www.tribuneindia.com/2000/20000312/spectrum/main2.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment