Kuldip Dhiman

|

|

KANZI, a bonobo chimpanzee, and Koko, a female gorilla, appear to have learnt to do something which most of us believe only humans can do: they can 'speak'. But can they?

If the video documentaries and other written material concerning these apes are any indication, Kanzi, his half-sister Panbanisha and Koko appear to have acquired linguistic and cognitive skills far beyond those achieved by any other non-human animal in previous research. These apes seem to be capable of comprehending spoken English utterances of a grammatical and semantic complexity equal to that mastered by a normal two-and-a-half-year-old human child. These amazing linguistic feats have made the scientific community and philosophers of language take a second look at the nature of mind and the origins of language.

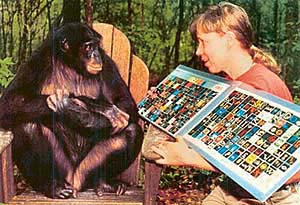

One of the first researchers who tried testing linguistic capabilities of apes is Dr Duane Rumbaugh. Since animals cannot speak in the real sense, as their vocal tract is not capable of making the kind of phonetic sounds we humans produce, Dr Rumbaugh came up with the ingenious idea of using lexigrams, which are printed symbols on an electronic keyboard. One of the first apes to be taught human language through lexigrams was Lana, who was born at the Yerkes Primate Center on October 7, 1970. A few years later, Dr Rumbaugh was joined by Dr Sue Savage (she was later to marry him), and for the last three decades , she has been studying and attempting to cultivate linguistic and cognitive capabilities of bonobo chimpanzees at Georgia State University's Language Research Center (LRC) in Atlanta, Georgia. And her star protégé, Kanzi has attracted wide attention of the public, professional linguists and psychologists.

Another Developmental Psychologist, Dr Francine "Penny" Patterson, began work with the one-year-old Koko, a female western low-land gorilla in the early seventies. She decided to teach the Koko American Sign Language (ASL) or Ameslan. Within a few weeks, Koko showed remarkable skill with sign language; by the time she was six months she was combining signs, asking questions, inventing gestures, spontaneously naming objects, and even talking to herself. Koko communicates her thoughts and feelings, says Dr. Patterson, using about 1,000 gestural words. By age six, she Koko had advanced further with language than any other non-human. Now Koko understands approximately 2,000 words of spoken English, and initiates the majority of conversations with her human companions constructing statements averaging three to six words. What is more, Koko has an IQ of between 70 and 95 on a human scale, where 100 is considered "normal." Both Koko and Kanzi and their siblings are now what we might call animal celebrities and have a huge fan following all over the world.

But is it right to say that these apes have acquired language and actually understand it? This is a hotly contested issue and critics of the ape language insist that no ape can ever develope truly linguistic skills, and that even the skills that Kanzi and Koko have manifested are more accurately termed 'performative' and 'effective', but certainly not 'linguistic'. The same can be said about parrots and other birds who in captivity pick up a few words of a language, and their ability is aptly called 'parroting'. Human language, critics assert, is an open-ended system of communication in which grammatical structure allows information of great complexity to be passed from one individual to another, and as far as we know, only humans can use it this way. Other species communicate with each other, and might transmit information about the world, but none does so with the degree of sophistication shown by the users of the simplest of human languages. Highly acclaimed linguist Noam Chomsky of Massachusetts Institute of Technology has repeatedly stressed in his theories that children in all cultures learn the language of the community in which they grow on their own with minimal help from elders, but this is something no animal seems to be capable of doing. They have to be rigorously taught by humans; unlike human children, on their own animals learn nothing. Besides, we use language not only to pass on information, we also use it to pass on disinformation or lies, we use it to tell jokes and so on. To have linguist ability in the true sense, the organism must have intentions, goals, beliefs, and must not only be able to convey them to others but also be able to read them from the minds of the others. Cognitive scientist Morten H Christiansen, Department of Psychology, Southern Illinois University, postulates that humans and other primates share certain fundamental cognitive abilities. Apes can learn fixed sequences such as the strings of sounds that make up words. They can also chop up the continuous sounds of spoken phrases in appropriate ways, but the similarity ends here. Humans are better at learning hierarchical structures than those of other animals. In the January 18, 2003, issue of New Scientist he argued that hierarchical structure was crucial for the syntactic processing of language because grammar requires the ability to build up a series of phrases into a meaningful sentence. This is something animals do not seem to be capable of doing. But what if it is proved that a particular animal has such capabilities such as intentions, mind-reading and so on, would we then grant linguistic capabilities to it? As philosopher John Searle put it, "`85. imagine a class of beings who were capable of having intentional states like belief, desire and intention but who did not have a language. What more would they require in order to be able to perform linguistic acts? The first thing that our beings would need to perform illocutionary acts is some means of externalising, for making publicly recognisable to others, the expressions of their intentional states. A being that can do that on purpose, that is, a being that does not just express its intentional states but performs acts for the purpose of letting others know its intentional states, already has a primitive form of speech act." This is the point animal language researchers are trying to get across to the sceptics. They say that the critics hold it as a logical truth that language capability is found in humans alone. So, no matter how much evidence Savage-Rumbaugh or Penny Patterson might amass, the sceptics will never accept that Kanzi or Koko are actually speaking. Why? Because they are animals. No one is trying to say that these apes use language with the same dexterity as humans do; certainly they are no match for humans. In the book Apes, Language, and the Human Mind, Savage-Rumbaugh says that although Kanzi is far behind humans in linguistic skills, yet he has shown that he understands abstract concepts, and can understand the meaning behind complex sentences, and can also indulge in playacting and pretending. His favourite pretend game centres around imaginary food. He pretends to eat food that is not really there, to feed others imaginary food. He pretends to find it, to take it from other individuals, to give it back to them, and to play chase and keep-away with an imaginary morsel. He will even put a piece of imaginary food on the floor and act as if he does not notice it until someone else begins to reach for it, then grabs it before they can get it. Whether Kanzi and Koko have acquired language skills or not, only further research will tell, but their achievements should not be ignored, just becuase they happen to be animals. As a well-read friend of mine who, in spite of his best efforts has failed to learn to speak English, said, "I wonder if these apes are better at language learning than I am." http://www.tribuneindia.com/2003/20031109/spectrum/main2.htm | |||

No comments:

Post a Comment